The New York transit agency has threatened to slash subway and bus service by 40 percent if it doesn’t receive federal aid. What could really happen is a bit more complicate

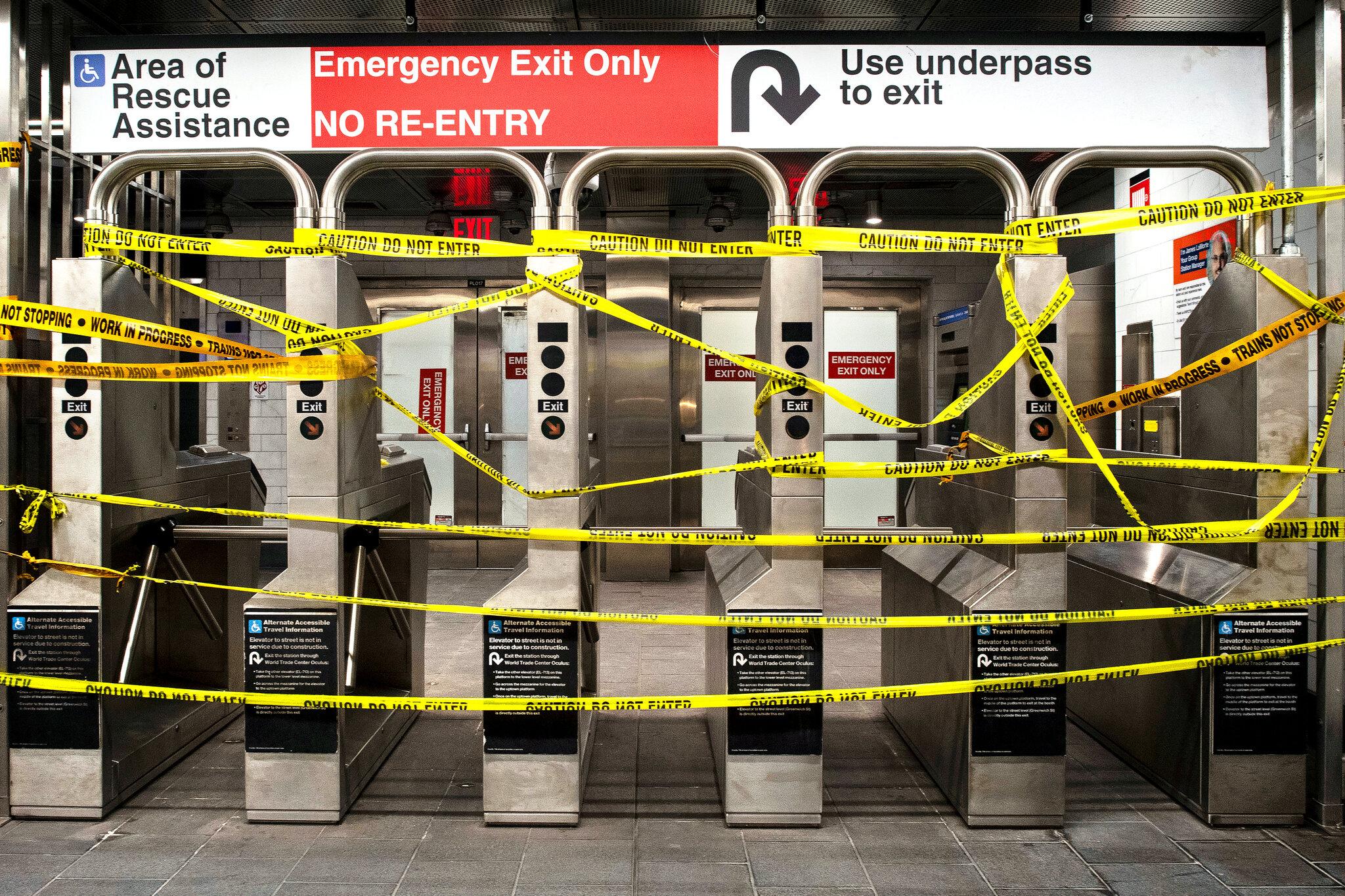

Since the pandemic plunged New York’s public transit system into its worst financial crisis, the transit agency has warned of devastating cuts, including slashing subway and bus service by 40 percent and cutting commuter rail service in half.

For months, transit officials have framed it as an all-or-nothing narrative — either the agency receives a $12 billion federal bailout or moves forward with its doomsday plan — as a way to place pressure on Congress, which remains deadlocked over another major stimulus bill.

But in practical terms the situation is not so black and white. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which oversees the subway, buses and two commuter rails, is likely to get at least some federal aid, which would avert the most severe cuts.

Still, anything less than $12 billion would force the agency to “look at everything on the table and make a decision as to whether service reductions at that level were still required,” Patrick J. Foye, the M.T.A. chairman, has said.

Transit officials are expected to offer more details about their plans next month when they are obligated to approve next year’s budget. Here’s what we know so far:

Bus routes and subway lines could disappear

While transit officials have not provided specifics, a look at past financial crises offers some clues about what could happen.

After the financial crisis in 2008, when the M.T.A. faced a much smaller $400 million deficit, transit officials eliminated two subway lines and 34 bus routes. Metro-North Railroad eliminated a handful of trains and the Long Island Rail Road reduced service on several lines, doubling wait times outside rush hour to 60 minutes.

To decide how to reduce service, former transit officials say they looked at bus routes and subway lines that overlapped to ensure that riders were left with some public transit option near their home — an approach transit leaders have said they would again pursue.

As in 2010, the agency has hinted that bus routes could feel the brunt of the cuts: Half of the more than 9,000 transit jobs that the M.T.A. has proposed eliminating would come from the division that runs buses.

This time, however, ridership will play a key role. With ridership at 30 percent of its normal levels, transit officials will seek to save money and adjust service to match current commuting trends and then gradually ramp up service on buses and subway lines as riders return.

Service cuts are not the only way to save money

The transit agency faces a $15.9 billion deficit through 2024, after revenues from fares, tolls, dedicated taxes and state and local subsidies practically vanished overnight when the pandemic hit.

The budget hole is the largest in the agency’s history, but some transit experts suggest that the M.T.A. — which has a reputation for massive overspending and labor redundancies — could address part of its deficit and stave off draconian cuts by operating more efficiently.

For example, the M.T.A. could run subway trains with one worker instead of both a conductor and an operator, as most train systems around the world do, or switch to a proof-of-payment model on commuter rails to do away with conductors who collect tickets. It could also reassess the system’s high cost for maintaining subway tracks and train fleets.

The agency has already found $1 billion in savings for next year by trimming nonessential services on the management side, like reducing overtime and eliminating consulting contracts, but it has not taken the same scalpel to the agency’s sprawling operations system.

“They’ve been going hard after administration, which they should — but operations are where the bulk of the money is,” said Andrew Rein, the president of the Citizens Budget Commission, a financial watchdog. The M.T.A. should think about cuts in terms of “efficiencies first and service level second,” he added.

But paring operations would require negotiating with transit labor unions that have fiercely opposed similar efforts in the past. Even if the unions agreed to concessions, any savings would not approach the billions in losses the agency is facing.

The treasury secretary, Steven Mnuchin, has suggested that the M.T.A. could borrow its way out of its financial crisis in the commercial banking market — a notion that many financial experts dispute.

Debt service already consumes about 16 percent of the agency’s operating dollars and more borrowing could eat further into the agency’s ability to spend money on running trains and buses, the experts say.

“If you rack up too much debt you don’t have enough money for your other operations,” Mr. Rein said.

Fares could rise by four percent next year

A four percent fare increase planned before the pandemic is scheduled to go into effect in the spring.

Transit officials are now laying out options for how the hike would be applied, including raising the base fare to $2.85 and increasing the surcharge for buying a new MetroCard from $1 to $3. The agency is also considering keeping subway and bus fare at $2.75, but either eliminating or increasing the price of seven and 30-day unlimited passes.

On commuter rails, options include keeping the price of monthly and weekly passes the same, but raising the price for single-ride and 10-trip tickets by more than 4 percent. Another possibility is overhauling the fare structure to create three new classes of tickets: Rides that begin and end in the city, rides between the city and the suburbs and rides that are within the suburbs.

The authority plans to hold virtual public hearings on the fare hike, which must be formally approved by the M.T.A. board, between Dec. 1 and Dec 21.

Officials have threatened that without federal aid fares may have to be raised even higher. But transit advocates have argued that doing so would raise little revenue if ridership remains low and would strain many of the city’s essential workers who are still riding public transit.

Major fare hikes could also discourage more riders from returning to the system, starving the agency of fare revenue.

Service will likely suffer for years or longer

Before the pandemic, the agency was pursuing an enormous $54 billion plan to bring the antiquated subway system into the 21st century, which included upgrades to train signals installed before World War II that are the source of constant problems.

That plan is now suspended.

Delaying improvements risks plunging public transit back into the state of disrepair that led Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo to declare a state of emergency.

Some upgrades will also become more expensive the longer the agency waits, which could affect how much the system can be modernized once it has escaped the throes of the financial crisis.

And because transit officials say they want to adjust service to match ridership, when and in what numbers commuters ultimately return to the system will help determine the level of service in the coming years. Ridership is not expected to reach 90 percent of pre-pandemic rates until at least 2024.

“We have the immediate crisis of Covid but then we have the longer term crisis of how the M.T.A. will adapt and change over the next several decades,” said Nick Sifuentes, executive director of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, an advocacy group. “A lot of the plans the M.T.A. had been laying to prepare them for the next generation of services are really at risk here.”

Christina Goldbaum is a transit reporter covering subways, buses, ferries, commuter rails, bicycles and all the other ways of getting around New York. Before joining The Times in 2018, she was a freelance foreign correspondent in East Africa. @cegoldbaum